So what is it that makes a man a MAN? Is it his chromosomal structure? His environment? Genetics? Wait… I know. It’s sports and videogames, right? Okay, okay, maybe not. I know! Sports, videogames and hot wings? Just kidding. I’m not quite that sexist. I know the male gender dynamic is far more complicated than that. Let me be the first to welcome you to The Myth of Macho, a series investigating the masculine image in popular cinema.

Quite simply, I have found that, in this day and age, masculinity is in need of critical study and not getting the serious treatment it deserves. I would invite you to come along with me each week as I look at some iconic films and figures within what might be classified as an American “macho” filmography and reconsider our notions of manliness and the male body on the whole. This week we’re going to be discussing Richard Donner’s Lethal Weapon (1987). Traditionally considered to be one of the more intelligent and fun action flicks, this film shines in the sense that it may be one of the few films I can think of that deals with male depression in a critical manner, all the while showcasing brilliant gunplay, fantastic villains (who doesn’t love Gary Busey as Mr. Joshua?) and explosions.

As a medium, cinema has served as the mainline for much of the iconography and ideology behind what we consider American Masculinity. From early swashbucklers and westerns to the most recent CGI-riddled action-adventures and spy-thrillers, it is the cinema that has worked its magic to establish what we commonly consider to be “The Ultimate Man.” While this can be entertaining to a certain degree, it can also be incredibly damaging. The American male is not some superhuman beast, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound (although I’ve met a few guys in bars who insisted that they were able to achieve similar accomplishments). If anything, the American Male, as he has been created by Hollywood Cinema, bears a much closer semblance to the turtle: tough as hell on the outside with seemingly endless durability, but fully vulnerable and sensitive just one layer underneath that outer sheath of “hard business.”

So what happens in the films that portray men losing that outer edge? What are we watching when we view films depicting that outer layer breaking down and shattering, exposing the raw, nerve-riddled center of the Masculine Identity? More importantly, what happens if that center is somehow damaged and/or broken? In this week’s Myth of Macho, we will look at a film that does precisely that as we discuss what it means to be a man in cinema, living on the edge.

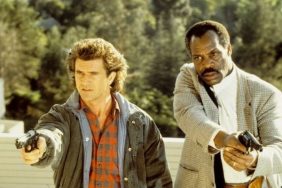

Lethal Weapon is primarily a buddy cop film. While much of the comedy aspect is predicated on the fact that Mel Gibson’s character, Martin Riggs, has a propensity towards being “crazy” and is known throughout the police force for his apparent death wish, while Danny Glover’s character, Roger Murtaugh, is the ultimate upper-middle class family man. This dichotomy alone would make for a decent film, but the pairing of the two men actually raises larger issues beyond those covered by the tenets and tropes of the “buddy cop movie.”

Released in the Spring of 1987, just one week before Evil Dead II (dir. Sam Raimi) and Raising Arizona (dir. Joel Coen), Lethal Weapon is a film that doesn’t pull any punches when it comes to the narrative arc. Writer Shane Black left all the “spice” to dialogue and characterization. The film follows a very basic story about Roger Murtaugh, a good, solid cop. He’s ready to retire, spend time with his family, have the good life. Then the “inevitable” occurs: our film. He gets paired up with Martin Riggs, a man considered to be a “lethal weapon” (thus the film’s title) in order to solve a case said to be suicide but seemingly quite a bit more like murder. As fate would have it, this case is intimately tied to Murtaugh’s own personal life and connections, becoming moreso as the film continues. This leads the two men into all kinds of exciting Los Angeles underworld elements: drug lords, prostitution rings, even a swimming pool heated by a solar-powered cover. While the team had been less than enthusiastic about working with one another in the beginning, as they trade off life-saving moments, they begin to grow attached and develop a relationship. For Riggs, whose backstory includes a recently deceased wife, an extensive term served in the Special Forces and a reputation for being the “insane cop,” having a “companionship of necessity” was not the worst thing that could have happened to him as we see within the film’s arc.

Lethal Weapon was incredibly successful upon release, maintaining the #1 spot in the box office for several weeks. Mel Gibson had done quite a few films previous to this, but none that really matched this as far as popularity was concerned. The film spawned several sequels, none of which was as successful as the first, possibly due to the fact that creative talent Shane Black was no longer the authorial mind behind the work. As of this publication, there are rumors of more to be made, but the reality is simple: the first will always be the best. It contained a certain magic, intensity and personal depth that can only really be achieved from a dramatic and comedic mix. The subsequent films never quite got the balance right.

Writer Shane Black knew what he was doing when he took the elements of these two characters and melded them together as a team. It is why this film works so well and continues to do so over the years. It is also why it is so important. What is that you say? Lethal Weapon is an important film? Why yes, yes it is. This film had the guts to pair up serious internal male conflict with badass action, a structural marriage that your average action flick wasn’t likely to be making at the time. I believe it is the portrayal of Martin Riggs’ loneliness, vulnerability and suicidal inclinations as well as the film’s discussion of the larger societal treatment of male depression that gives Lethal Weapon some of its most incredible staying power.

It’s hard to talk about mental breakdowns. It’s doubly hard to talk about loneliness. Coming out about depression? That takes years for most people. Now take all of that and multiply it by, oh, masculinity. Then you have a place that I can’t even imagine being at. I think women have it easier on that front. The ways in which we are expected to synthesize emotional conflict according to our gender are quite different than those of men.

Gender performance and emotion have very different rules for men and that worries me greatly. This deconstruction is, of course, a grand generalization so if you’re one of those guys who totally cried after every Pixar film, that’s completely awesome, please ignore. According to what I have titled “The Rules of Masculinity,” it seems to me that, on a larger societal level, crying and similar displays of emotional pain have been firmly established as demonstrations of weakness. These are seen, by the “world-at-large,” to be bad, as men are robust and solid creatures and the concept of manliness should always be equated with the concept of being impervious to emotional fragility.

By this logic, not only is it odd but it is rather innovative for Lethal Weapon to platform a protagonist whose male core is not only cracking (or cracked) but vulnerable and raw. The Rules of Masculinity maintain that an action film is about strong, virile men kicking ass (which, for all intents and purposes, Lethal Weapon is indeed about on the basic narrative front, so it does certainly keep up that façade). But what of the fact that the film’s pivotal point is based upon the quite notable detail that Martin Riggs (Mel Gibson) is, himself, not a “strong” man? By virtue of the fact that he is depicted as being suicidal (both privately and in the public working eye), his mental health is questionable.

Within the narrative, Riggs’ mental dysfunction corresponds with the depiction of him as being incomplete. Where Murtaugh has a family, Riggs flies solo. Where Murtaugh is characterized as being stable, Riggs is considered “off.” Where Murtaugh’s domestic setting is rich and pleasant, Riggs’ home setting is empty and fallow. These oppositional characteristics develop the yin/yang element within the narrative and assist in the “buddy cop” theme, but they also illustrate Riggs’ positioning. They make Martin Riggs’ trauma a key function of the film as a whole.

Depression causes severe decay in the human condition. If there is nothing to keep you going and you don’t have some kind of ethos or drive telling you to “keep at it” you are more likely than not to stay fetal, in your cave, pajama-clad, never leaving. But if you do have something… it may be a different story. Glancing in on Martin Riggs in the first scenes in his trailer, one would be hard pressed to argue that he is not depressed. He certainly doesn’t care enough to put any energy into the state of his life or surroundings. Why should he? And yet, as we discover, he is a functional depressive.

As the film continues, it’s clear that he is not one of those “curled up in a ball, stay-at-home” types. Nope. Martin Riggs, regardless of personal issues, has an extremely strong work ethic, and, as unbalanced as he is, he will show up, be there, do his job and get it done. It may not be according to standard practice, but you could never say he didn’t show. This fact, however, does not make him any less depressed. As he tells Murtaugh, “Well, what do you wanna hear, man? Do you wanna hear that sometimes I think about eatin’ a bullet? Huh? Well, I do! I even got a special bullet for the occasion with a hollow point, look! Make sure it blows the back of my goddamned head out and do the job right! Every single day I wake up and I think of a reason not to do it! Every single day! You know why I don’t do it? This is gonna make you laugh! You know why I don’t do it? The job! Doin’ the job! Now that’s the reason!”

His first public assignment with Murtaugh (Glover) displays the kind of conduct associated with people who have been diagnosed as suicidal. To an extent, much of Rigg’s “acting out” may translate to his peers as “crazy” but actually is more reflective of a kind of mania, a symptom quite easily tied in with severe depression. The behavior he exhibits might have been stigmatized by the other policemen and women in the force as certifiable but is actually a great deal more serious due to the fact that being considered mentally unstable is a taboo topic and one that is not discussed very often at all, let alone in the workplace. Their synthesis of Riggs’ situation is simply to laugh it off or ignore it because the mere mention of something like mental illness might make someone in that line of work extremely nervous. Perhaps moreso than your average citizen, due to the high frequency of heavy violence and emotionally disturbing activities they see and/or perform on a daily basis. So ignoring Riggs’ “craziness” is a defense mechanism. But when it comes down to it, any individual who would knowingly participate in this kind of performance at work is very likely suffering from mental dysfunction, whether or not his co-workers want to see it.

As Murtaugh and Riggs pull up to the incident, we see a man about to jump off the top of a very high building. While the other officers follow procedure, Riggs crawls out to the ledge and begins to talk with the jumper. By the end of the conversation, not only does the jumper think that Riggs is insane, but Riggs has managed to cuff himself to the man and is asking him if he really does want to jump. Confronted with a cop who is ready to take the leap as well frightens the jumper and he no longer wishes to take his own life. But before any alternate decision can occur, Riggs “talks the man down” …by jumping. While they land on the conveniently-timed police airbag, Riggs’ immediate response is “C’mon, let’s do it again!” while the jumper screams, almost incoherently, “Did you see that? He tried to kill me!” Riggs stands there, grinning.

While he may have known the airbag was there, the exchange between the two men up on the ledge made it perfectly clear that Riggs couldn’t have cared less. His monologue contained a number of “buzzwords” that made his own situation plain as day. While he may have been “doing the job,” and dealing with a jumper, his entire approach centered around his own personal issues. Within the conversation, Riggs mentions the holidays being a rough time, says he knows about the guy’s pain (“I get it”), and, just before the jump, he looks at the jumper, wild-eyed, and says: “Do you really wanna jump? Do ya? Well then that’s fine with me… Let’s do it, I wanna do it, I wanna do it,” and off the ledge they go.

This may be marked as an example of how unstable the Riggs character is and meant to show his erratic behavior, but it may be more productive to view this scene from the context of the way in which it underscores Riggs’ emotional state and how he reveals his secrets to a complete stranger up on a rooftop. He has no one to talk to, no one in his life, no one to go to, and, while he is making attempts to save this man as part of his job, he is also reaching out to him. While it may be the only way to get the man down, the jump also shows how deeply Riggs himself is in crisis. His situation is, in reality, not much better than the man he is “helping.” In many ways it is worse. No one expects the jumper to do anything but recover from the suicide attempt. For Riggs, people expect much more; he is the cop/authority figure.

Even if Riggs is considered to be “crazy,” he is still expected to function at his job, through unconventional methodologies or not. If Riggs had been shot or had cancer, the entire force would have a different attitude towards his recovery. However, in the case of mental conditions, whether caused by PTSD, depression or any number of other catalysts, he is simply passed off as “crazy” instead of the force recognizing that he is actually in great amounts of emotional pain. While one scene in the very beginning of the film does show a therapist objecting to his presence in the field, she is very quickly pushed aside and ignored. That says quite a bit. It seems that even when there are warning signs that point to an officer’s volatility (because certainly no one is looking to his actual health, heaven forbid) the concept that his ability to finish the job “by hook or by crook” wins out. Additionally, this scene also speaks to the fact that, by having to face Riggs’ instability and put him on leave, these higher officers would have to face a kind of collective fear of the job itself being the cause of his disorder, as police work is an extremely high-level stress environment. The “I’m sure he’s fine” mentality stems not only from not wanting to ignore mental health issues because they are taboo on a social level, but also on a more institutional and systematic one.

When discussing Riggs’ battle between his depression and ability to maintain himself as a masculine figure, Lethal Weapon’s most powerful sequence is when he is alone at home watching cartoons. He comes very close to committing suicide. For 1987, this scene seems especially heavy, especially for an action film and even moreso for a buddy-cop film. To be perfectly frank, it still seems pretty heavy. However, during that period of time there were just not many action films that “happened” to include a sequence with one of the main characters in his trailer, holding a framed photograph of his dead wife, carefully loading and placing a gun in his mouth, and then crying his eyes out.

Bits like the suicide sequence are why I argue that Riggs is not “crazy” and that this character is quantifiably more complex. The discussion of his mental condition in the film is something that, much like masculinity and depression in general, gets somewhat overlooked. Within the narrative, instead of someone investigating to see what would create the “loose cannon” in the field, they simply accept him as the “loose cannon.” While that makes for a great film, Shane Black’s periodic references to Riggs’ state of mind do serve to remind the audience that he is not crazy and that he is actually a man who has suffered extreme traumatic experiences, whether they were due to military service or his wife’s untimely death. The scene in which he loads up the gun and prepares to shoot himself is methodical, preparatory. It is one that, from the looks of it, he does regularly. However, it is unclear to us, as viewers, how far he usually takes it. Was this night further than usual? Was that why he sobs (and he does, quite literally, sob), “I miss you, Victoria Lynn. That’s silly, isn’t it? I’ll see you later, I’ll see you much later.”

While Lethal Weapon’s primary goal was not necessarily to investigate ideas of depression or mental illness in male authority figures, it was a positive outgrowth of the film. While we can all recognize that Lethal Weapon has cultural value as being a well written and exciting action film, the fact that it can be studied on another level usually reserved for taboo gender-dynamic subject matter makes it even more fascinating. By endowing Martin Riggs’ character with psychological ailments and trauma and then allowing the audience to endure multiple private experiences with him, Shane Black aligned us with him, and placed us within the “stigmatized” camp. While we are definitely on Roger Murtaugh’s side, we feel more for the “crazy guy,” meaning that we have now been given the ultimate experience: we now have a small, intimate glimpse of what it might look like to be a suicidal cop, with all the trimmings.

In doing this, the filmmakers have created a space in which we are able to balance our feelings of admiration for Murtaugh and our affiliation with Riggs. While we may not feel that way throughout the sequels, we certainly feel this way in the first film. We synthesize Martin Riggs’ trauma, loneliness and depression and its relationship to his highly masculinized career choice of law enforcement but also to his intense past in the military. We study his bond with Murtaugh and the way that it unfurls into a way of healing open wounds, perhaps intimating that male bonding or even simple healthy human contact is a way of relieving situations of extreme crisis. All of these issues, however, are done through our being positioned with Riggs, the character who is (for all intents and purposes) considered to be the “lethal weapon.” A valuable comment on the way to look at the mental condition of male characters within cinema and even moreso, how we are located within as viewers.

Please join me next week for another muscle-pumping, action-swinging, sweat-building installment of The Myth of Macho. After all, the brain is a muscle, right?