Penny Dreadful is back in Stan’s brand new series Penny Dreadful: City of Angels, in spirit, that is. While the spooktacular tone of the cult original series remains the driving force, this time around the show has traded currency, and motif – the “penny dreadfuls” of 19th century Britain now giving over to the dime store detective novels of 1930’s interwar America. A little bit Raymond Chandler, a little bit H.P. Lovecraft.

“City of Angels” takes us to 1938 in the eponymous city of Seraphim, Los Angeles. The Golden Age of Hollywood is in full swing, FDR’s New Deal is turning the US into a superpower, and cultural tensions between Anglo-Americans and Latinos are at the highest they’ve been since the Alamo.

In short, it’s the Devil’s playground.

“City of Angels” explores the duality of human morality – life and death, light and darkness, vanilla and chocolate – so we thought we’d take a look at historical and mythical roots of the Mesoamerican cultural spiritual dichotomy through their stereotype-smashing anthropomorphic personification of death – Santa Muerte. Nuestra Señora de la Santa Muerte – Our Lady of the Holy Death – is a key player. In fact, it’s the title of the series premiere episode.

A pale skeleton wielding a scythe, she shares some passing similarities to the European figure of Death, but that’s where the resemblance ends. Santa Muerte is no Grim Reaper. Her robes are not black, but colorful (although which color depends on who is looking); and instead of being a feared spectre of mortality, Santa Muerte is revered as a figure of love, prosperity, and protection (more recently, in a sign of the times we live in, this has become synonymous with protection from bullets), making Santa Muerte an obvious choice of worship for those who move or work in environments where danger lurks; or those or care for them. An example of the omnipresence of this worship in the world of “City of Angels” can be seen in the fact that Detective Vega’s mother, Maria, has an altar to Santa Muerte in her house.

While her scythe is used to reap the souls of the departed, it is viewed more as a symbol of hope and rebirth: it is, after all, a key tool used for a bountiful harvest of life-giving crops. She carries a lamp to banish the shadows of ignorance and doubt. Her familiar is the owl, a creature of wisdom, but also a predator who sees clearly in the darkness.

Nothing embodies the turbulent melting pot of cross-continental cultural clash, another prominent theme that depicts the city’s simmering racial tensions and the triumph of the human spirit better than the evolution of the figure of Santa Muerte. She is the result of the violent collision of restrictive, dogmatic Catholicism with Aztec mythology, a religion noted for its violence and brutality.

The Aztec pantheon is a complicated one. They have two water gods – one for vertical water, like rain, and one for horizontal, like rivers. There’s the god of war – Huitzilopochtli, but then there’s also the god of war for colonial purposes, Xipe-Totec. Then there’s the Aztec fascination with death, which would ultimately give rise to the figure of Santa Muerte. There’s Xolotl, he’s the god of death. Mictlantecuhtli, he’s also a god of death. And, because of the rule of threes, Mictecacihuatl – goddess of death.

The Aztecs liked to have their bases covered. It was a religion built upon the concept of duality, with every godly portfolio having a good and a bad aspect. Death also meant an eternal, blissful afterlife. War and destruction presented an opportunity to rebuild. The rains that watered crops could easily turn into devastating floods. Heads and tails, but always the same coin.

When the conquistadors sailed the Atlantic and brought with them peak Christianity, it wasn’t that much of a mental shift for the people of Mesoamerica. A strict, dogmatic religion with a clearly defined hierarchy, minimal social movement, exultation of martyrdom and an emphasis on suffering in this life to earn reward in the next – it was just a matter of rebranding. And rebranding is exactly what happened. As happened in other parts of the world conquered by Abrahamic religions, individual gods and goddesses became saints. And in one notable instance, Mictecacihuatl – the skeletal goddess of the dead, their protector and their guide to the hereafter – became Saint Mictecacihuatl and eventually, just the saint of death.

Santa Muerte is the result of what anthropology calls a ‘cult of crisis’. She is a patron saint of the poor, the destitute and the luckless, and her popularity skyrockets during times of economic crisis. Times like the current ones. To those who have fallen through the cracks, or those who see no way to escape poverty, Santa Muerte is seen as a bringer of equality and justice – death is the greatest leveler, as, at the end of the game, the pawn and the king go back in the same box. The duality of her character can often cause a crisis of faith, particularly when misfortune or untimely death strikes those who pay her worship, and thus believe themselves protected. Detective Vega feels betrayed by Santa Muerte when his father dies in a crop fire.

The White Lady is a powerful entity invoked through making offerings to a figurine or statue in her likeness, usually in the way of food, alcohol or money. Her protection is often sought by those who brave the dangers of the night, such as police officers (hello Detective Vega), taxi drivers, bar owners, prostitutes, and gangsters – when big-shot Mexican criminal Daniel Arizmendi “El Mochaorejas” López, whose story was the subject of 2004 film Man on Fire (you’ll have to look that up yourself, definitely NSFL) was arrested, his home was found adorned with a shrine to Santa Muerte. Since this was discovered after his arrest, one can only speculate as to how effective the protection of The Powerful Lady truly is, or who was under her protection.

Santa Muerte may be a figure of death, but her passion is life – both on earth and in the hereafter. She is a maternal figure, a guide and a protector, who furiously defends her charges and fights those who would do them harm. She is the guardian of the cycle of life and death, the balance of the hourglass, and woe to she who would seek to upset that balance. In the case of City of Angels a certain shape-shifting, demonic influence named Magda.

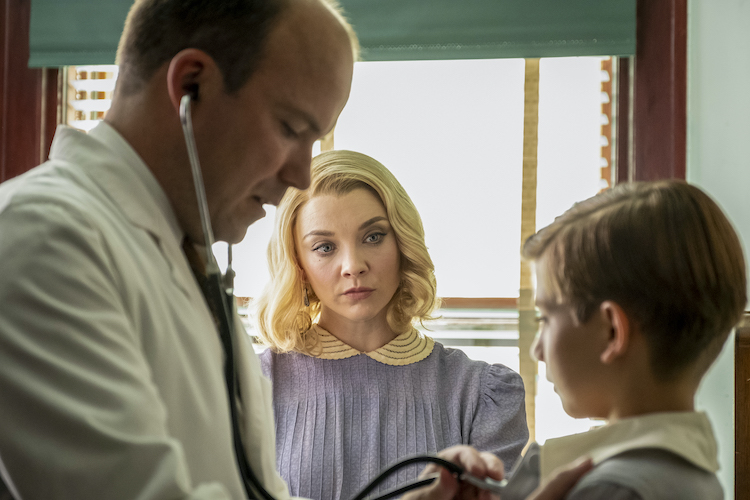

Thus begins our premiere episode of Penny Dreadful: City of Angels as we meet the shapeshifting demon Magda (played by Natalie Dormer) and her sister Santa Muerte herself (portrayed by Lorenza Izzo), both of whom find themselves embroiled on either side of the battles of humanity around them. What promises to make it most complex, is that unlike the wars for which both Aztec and Abrahamic constructs were built upon, the battles of Penny Dreadful: City of Angels have no obvious sense of balance, no two sides of a coin. These are wars of race, of class, of family, of religion, of nationhood; brought to the surface by not just Magda, nor the fallibility of men alone, but by the most quintessential of American gods, capitalism.

To find out how this plays out, well, you’re just going to have to tune in yourselves.

Photos: Courtesy of Showtime

The brand new series Penny Dreadful: City of Angels is now streaming, with new episodes the same day as the US, only on Stan.