To celebrate the upcoming President’s Day holiday, we asked our panel of film critics – Crave’s William Bibbiani and Witney Seibold, and Collider’s Brian Formo – to present just one film each that stands out as the very best movie about American Presidents, and as usual, they couldn’t agree on a thing. Find out what they picked and why, let us know your favorites, and come back every Wednesday for more debatable topics on The Best Movie Ever!

Brian Formo’s Pick: Advise & Consent (1962)

Columbia Pictures

Fictitious movie presidents are often too good to be true – showing our best qualities as Americans personified in the body of someone who can both speak eloquently and whom you’d also “want to get a beer with” – or too horrific to be believably elected, thereby showing our national distrust of elected officials. So for me, the best movie involving an American President is one that sidesteps all of the above and just places the President in a standard Presidential situation – submitting a Secretary of State for Senate approval – and watches how the individuals in Congress form alliances to either block or accept his appointment.

Otto Preminger’s Advise & Consent is perhaps the most illuminating film about American governance ever made. The themes of McCarthyism and homosexual paranoia, surrounding a potential confirmation of a President’s appointment (played by Henry Fonda) still resonates but most excitingly there is no labeling of Democrat or Republican. We have been divided as a country for more than a century and Preminger wisely does not want audience members to lose focus and align themselves with characters early on solely based on party affiliation. Listening to a Southern constitutional blowhard (played with gleeful bluster by Charles Laughton) you’ll probably naturally place him in a certain party but Preminger wants you to focus on how both sides reframe positions to get what they want. There isn’t a better party on display here; there are some Senators who are better schemers and some who wrestle with their conscience. And they’re in both parties.

Preminger was an Austrian filmmaker who was summoned by Hollywood to come to America before WWII broke out. He’s most well known for his magnificent film noirs and filming classic operas and musicals with an all black cast, re-contextualizing the universality of the theater, but with Advise & Consent (and Anatomy of a Murder), Preminger showed a surgical precision in dissecting the American processes of law and order. That patience and desire to view a situation from every angle is what makes Advise & Consent so revelatory. It also places the President (Franchot Tone) right where he should be: waiting for 100 individuals to keep him in check. And provide balance.

Witney Seibold’s Pick: Idiocracy (2006)

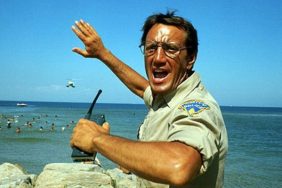

20th Century Fox

There have been many films about the way the highest office in the nation operates, and there have been plenty of wonderful fictional and non-fictional presidents presented on screen, from JFK and Nixon to Dave and the Jack Ryan movies. Most stories about American presidents, however, tend to treat the office as something Olympian and far away. Something insurmountable. It’s as if the Ordinary Man could never hope to fully understand the presidency, nor the Great Americans who may occupy that office. Movies – no matter how good or bad they may be – tend to treat presidents the same way the hoi polloi looks at celebrities; we have to constantly remind ourselves that a president is Just Like Us. We tend to elevate the nation’s most public figure into something grandiose.

The presidency, however, is, in actual practice, much more a reflection on the American people than it is a portrait of the nation’s champions. Whoever resides in the Oval Office tends to be a reflection on where American culture is at the time. Presidents affect culture far more than most people realize. So an accurate film about a president would show how the commander in chief would interact with the people. How s/he would look on the ground, talking to everyday people, no longer campaigning.

As such, one of the most memorable, accurate, and enjoyable depictions of a cinematic president may be from Mike Judge’s Idiocracy, a dystopian fantasy about an average man from the present who wakes up in a future ruled by the lowest common denominator. The film is cynical and fun at the same time, warning audiences of the way ignorance can proliferate. The president in Idiocracy is President Camacho, played by Terry Crewes, who cusses, fires machine guns into the air before addressing the nation, and who bellows like a televangelist. What sort of man would a nation of low-brow people elect? Someone like this. Camacho was meant to be a distant spoof of George W. Bush (who was in office when the film was made), but he could stand for any politician you hate. Camacho shows that we get the president we ask for.

William Bibbiani’s Pick: Lincoln (2012)

Walt Disney Studios

The President of the United States isn’t a title, it doesn’t denote royalty, and it comes with no guarantee of greatness. It is now, has been and always should be a really hard job that no one in their right mind would want unless they felt compelled to serve the people of this country. But what happens when the country wants something morally reprehensible? How do you serve the needs of the people but not their desires? How do you be “presidential” in amoral times?

Many presidents, Barack Obama included, cite Abraham Lincoln as an important influence. Steven Spielberg’s impressively nuanced, rarely sentimental biopic Lincoln illustrates why. A skilled statesman and well-educated lawyer, the 16th President of the United States – played by Daniel Day-Lewis with a deep sense of humanity and a keen awareness of the man’s mythology – Abraham Lincoln goes to extreme lengths to abolish slavery, always aware that he’s gaming the system but never venturing too far into illegality for fear of invalidating the outcome. Changing the Constitution is supposed to be a difficult process, and convincing people to act in the interests of humanity often requires complex politicking and personalized appeals to their individual vanity and self-preservation.

In other words, doing the right thing is incredibly difficult. Doing the wrong thing is comparatively, and despicably easy. Lincoln tells the tricky story of how our most celebrated President served the best interests of the country even though half of America hated his guts at the time, sending us out on a road to social progress. It’s a journey that helped define this nation as a place where equal rights – which, despite our explicit declaration, were not available at our country’s outset – were the noble goal to which all Americans could claim to aspire. We still work, constantly, to make America a more equal and tolerant place to live, and sadly it doesn’t seem to get any easier.